(Image of unicorn via Cartoon vector created by freepik – www.freepik.com )

It doesn’t matter where I’m standing, the type of object I’m about to throw away, or which hand I’m throwing with. I always make it into the trash can (well, almost always). It’s become a standard joke of mine when people raise their eyebrows in amazement at my ability to consistently “make the basket”: “That’s what happens when you do Anesthesia for a long time.”

All kidding aside (and by the way, I do not try this with sharp objects!), my garbage-throwing accuracy got me thinking about all the skills I’ve honed over years of practicing my specialty of anesthesiology. Despite being a part time physician now, I’ve worked thousands of cases, both in and out of the OR, for more than 10 years. With time and sweat equity, you truly become an expert in your field of work – no matter what that field is. But there are also subtle skills, some that cross over into my non-work life, that have showed up too:

- I know how to get people to warm up to me quickly. When performing a preop assessment and consent for anesthesia, I have to get patients (and potentially other family members) to trust me with something very precious: their lives. And I only have about 10-15 minutes to do it. Over the years, I’ve learned how to ask questions, make little jokes, and explain my anesthetic plan in such a way that patients of all types feel comfortable with me. This skill translates over to everyday interactions with people: a fellow mom at preschool, the tire guy at Costco, a clerk at the grocery. Despite being an introvert, I end up making friends in a way that I never did as a young adult.

- I can read people’s level of receptivity to complex information. Pursuant with 1) above, I’ve learned when to give more detail about anesthesia vs. stop at the basic information. When I first start talking with a patient, I can gauge their level of interest and understanding – not only about what my role is in their care but also just their own basic health status. Surprisingly, some people are very unaware of their own medical problems. I view this with non-judgement and explain things accordingly. This ability to modulate my communication style translates to interactions with friends and family as well as phone calls and business transactions. Sometimes the best thing to say is nothing, and I’m pretty good at figuring out when those times are.

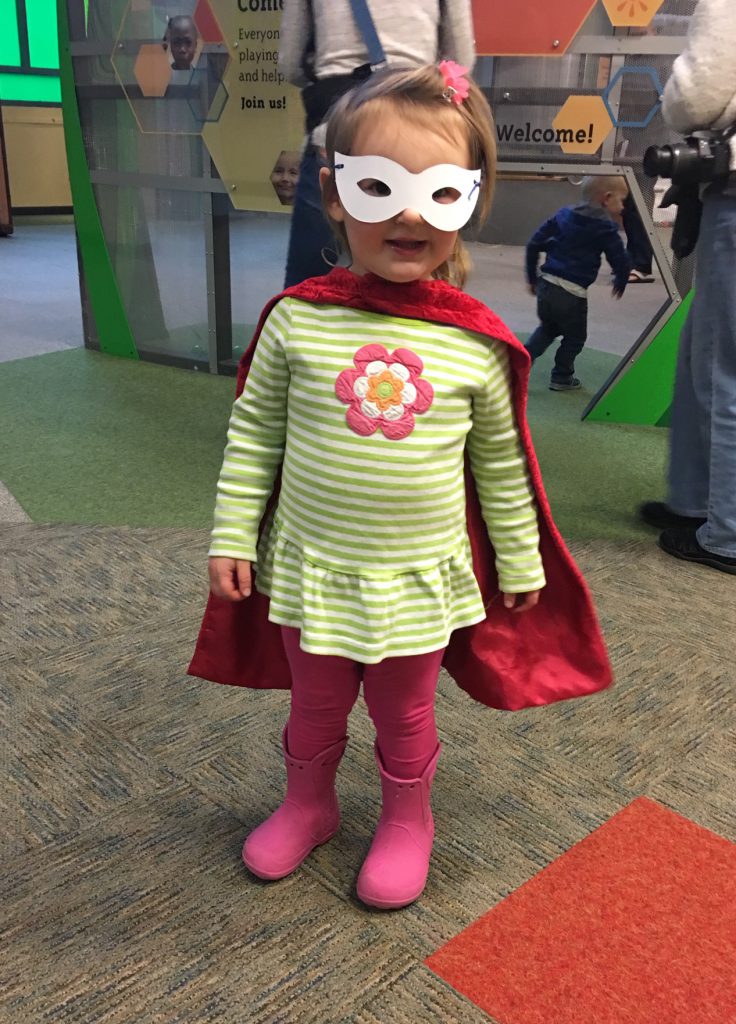

- I’m a mega multitasker. After I get a case going, I optimize my patient’s ventilator settings, give drugs to stabilize their hemodynamics, position them in an ergonomic way, set up a means for warming them, draw up more drugs, get ready for the next case, and chart on the present case all at the same time. Multitasking is a huge part of my job. Anesthesiologists develop a keen sense of hearing – a slight downturn in intonation of the oxygen saturation monitor, for example, perks up our ears when we have our backs turned to the monitor preparing medications. Same thing goes for home life: you can often find me looking up cases for the following workday while making my daughter’s preschool lunch and doing the dishes… all of which I might interrupt when I hear a faint, muffled cry from the bathroom from a certain toddler who needs my help. You know how they always say that moms have eyes in the back of their heads? Anesthesiologist moms have eyes and ears and hands in the back of their heads!

- I employ a mean mise en place. The term mise en place refers to a cooking technique that translates to “everything in its place”. As Gretchen Rubin reminds us, it’s also a state of mind for how we can organize our lives. In anesthesiology, it’s extremely important to be efficient and organized. If you don’t have all your drugs labeled accurately and positioned in a recognizable pattern and location, you’re likely to commit a medication error. If you get two of your nine patients’ medical histories for the day confused, you’re likely to develop an inappropriate anesthetic plan. If you fail to find a vital piece of equipment in your cart during an emergency… Utilizing mise en place has crept into my daily life outside the hospital, necessitated also by being mom to a toddler. I’ve downsized my wardrobe and other possessions to fight decision fatigue and mental distraction, and I’m able to find things much easier at home.

- I’m calm under pressure (to a certain point). It’s not that I’m always calm. In fact, I’ve been known to utter a four letter word or two during a difficult procedure or an unstable case. But what I have learned how to do over my years as an anesthesiologist is quickly assess an adverse event and know if it’s going to turn around without harm or if it’s going to spiral into badness. I know which blips on the normal radar will harm my patient and which won’t. We’re trained to call for help early and often, and we develop a sense of when it’s necessary to do so. Conversely, a little dip in the oxygen saturation reading after an intubation isn’t something to worry about when I’m actively taking steps to reverse it. The other day, my daughter broke a mug and cut her finger on the shards. She freaked out at the sight of the blood, but I ran over with a cloth and cleaned it, covered it, put pressure on it… reassured her. It will stop bleeding. Cuts always stop bleeding, unless they’re really really big. It’s going to be ok, give it a few minutes.

It’s often said, “The way you do one thing is the way you do everything.” I’d say that for a lot of the above, this statement applies. But admittedly, I could be better at home about my organization and decision-making. The scaffolding is there, so I now that I’ve reflected on this, I need to apply those practices that seem so innate at work. On the other hand, it would behoove me to further unlearn the multitasking skill for home. Multitasking can sometimes lead to distraction toward some tasks but away from family members. Putting down my phone each night for a period of time, doing yoga and meditation help to bring unitasking back into my life, but I could be still be better about slowing down and looking away from the ever-expanding To-Do list.

Another important skill I have, which didn’t necessarily come from my work as an anesthesiologist but more likely from life experiences such as becoming a mom and being a patient, is to know how to take care of myself. I know that my work quality will suffer if I don’t prioritize sleep, exercise, and good nutrition. I have to focus and solve complex problems at work, so it’s imperative to be fresh and healthy. And if I’m not, the consequences stand to be severe.

What about you? What are your superpowers acquired with life experience (either work-related or not)? Share them in the comments!

[A version of this blog post appeared on the website Doctors on Social Media. You can view it here.]

You Don’t Have To Hustle

You Don’t Have To Hustle

I do find that there is a lot of bleed over from skills I derive from work and what I use in normal day to day operations (in fact in a month or so I have a multiparty series I already wrote and plan on publishing describing those very things).

It is surprising how one skill set can then be used to benefit another in the least likely of circumstances.

Cool, I look forward to reading the series! I’m sure this type of things crosses over to other specialties and careers.

Hi Dawn

My superpower is Habit Mastery:

I wrap good things to do into habits, and they stay unless updated or dropped as needed.

Sample goodies:

– while brushing your teeth, do it in a squat position

– while having your coffee in the morning (at home)/midmorning (at work) /afternoon (at work), do it in a kneeling position (to improve your dorsiflexion) and change to seiza position (aka hero’s pose) after a while

– and you get the idea 🙂

Wow that is brilliant, thanks for sharing. Pairing habits together seems like a great strategy for making habits stick. You don’t know how much I need to work on my ankle dorsiflexion!

I love this post and also want you to adopt me because you are probably the most amazing mom with these skills!

I think pressure drives a lot of people to perform in general, but I think people who thrive in these conditions are drawn to fields like ours- those that require focus under pressure. In interventional radiology, you need to be excited by catastrophe, not paralyzed by it. I think that’s an IR superpower.

Hi Barbara! Having anesthetized patients in the IR suite, I definitely agree with your “excited, not paralyzed”-by-catastrophe superpower! I’ve seen it in action!