I’m 44, and in my adult life I’ve taken something like six “sabbaticals”.

Upon hearing the word sabbatical, one traditionally thinks of a university professor taking a paid leave for one year, approximately every seven years, in order to complete a special project or write a book. But the best and most general definition I found, rooted in Latin and Greek language, is from Wikipedia: “a rest from work, or a break, lasting one month to one year.” By this definition, we’ve all taken sabbaticals – when we were children, every summer. And what did we do? We played. We recharged. We learned a new skill (I personally spent a few summers in elementary school taking swim lessons and learning all the strokes). When we got older, we may have engaged in some personal improvement projects to benefit us for the next school year. Sadly, these types of sabbaticals are fading away into our hyper-scheduled, always-on lifestyle, even for young children. We’re setting our kids up for a life of stress and the real possibility of burnout.

An unpaid sabbatical is becoming a more common benefit at some major employers, but the reality is that most people barely even use their two-ish weeks of allotted vacation. This article gives some sad statistics about Americans leaving vacation days unspent, feeling scared to take the time off, and loathing the pile of work they will return to after even just a few days. I’m fortunate to have a job with lots of (unpaid) time off so that I can take what I would call ideal vacations, but sometimes you just need a longer break. Sometimes you need a reset, due to a major transition or other reason. Nowadays, it’s rare for people to stay at the same job for years and years. Why more people don’t take extended periods off in between jobs is beyond me, and if you’re one of those to have a great employer that you’ve been with for several-plus years, maybe you should ask for a sabbatical. The worst thing that could happen is that they say no!

Here is a recount of my sabbaticals, each one involving revelations or major life pivots that loosely lead to the next. This string of sabbaticals has ultimately shaped who I am today.

#1

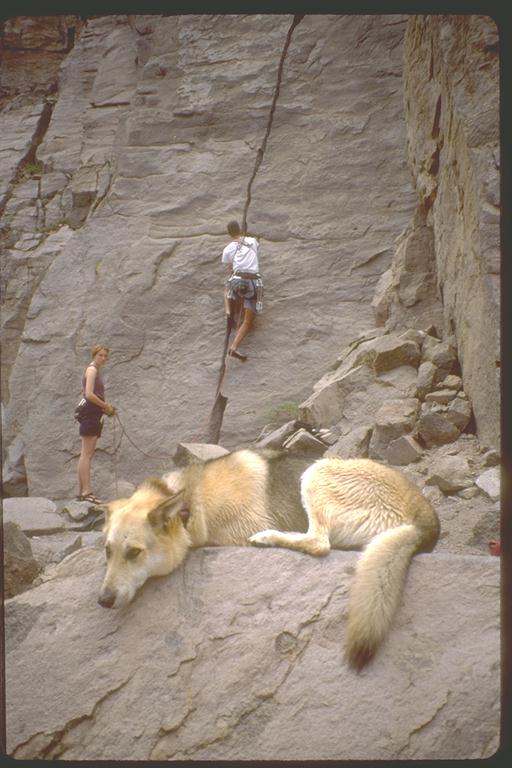

As a 22 year old, fresh-faced chemical engineer in between jobs, I took my first sabbatical. If I hadn’t been with my boyfriend who was the perennial questioner and forward thinker, I would have never done it. Knowing nothing about negotiation, I was so scared to even ask for the delayed start to my new job. I remember my dad saying, “But there’s going to be a hole on your resume!” [Cue stern dirty look at said boyfriend, who was “ruining everything”.] But the company didn’t even bat an eye. We spent three months traveling the western US in our beat-up old travel trailer named Betty. We visited family we never see and rock climbed in places we’d never been. I realized on this trip that we can form close bonds with people who are much different in age. Climbing gifted us with friends from 18 to 65, and all I knew before this was the homogeneous, age-based classes we’re forced to stay with during our childhood years in school. We also met intelligent people (not mere bums or hippies) living on the road, scraping by with very little funds, simply happy to just be outside climbing. I had never seen anything like that before.

All was well when we returned; nothing bad happened! My job offer was not revoked! The boyfriend started law school and I started my new job.

#2

I ended up going to graduate school a few years later, and I married that boyfriend. Shortly after our late spring wedding, he had to be in California for a summer clerkship with a prestigious firm. Then he had another one in Salt Lake City. I arranged with my lead professor to go along. It was a stretch; my proposal was to use the time to perform in-depth literature search and writing for my thesis, in addition to doing a few experiments at an affiliated lab in LA. They agreed to it. (Of course, we also wanted to revel in our newlywed-ness, go surfing every day, and explore cities where we might consider moving.) That summer, we lived in Betty in a trailer park under the commuter rail, 10 minutes from the beach (the only reasonable short-term living arrangement we could find on a paltry grad student budget).

I only stood up on the surf board for about 10 seconds at a time all summer, but this sabbatical taught me a few important things: 1) After being spoon-fed my education for my entire life, I CAN be self-directed in my own learning. 2) Trailer park life is a bad cliche but is nothing to feel ashamed of. With some diversity in age and background, we’re still all humans who need a place to live. Essentially, this was the first time I realized that we weren’t any different than the other people there. 3) Life is fleeting, and we are not immortal (a hard lesson at 25). My husband’s childhood best friend and fiancee, wedding planned to follow soon after ours, were killed in a tragic car crash that summer.

#3

At the culmination of my husband’s law degree and my Master’s thesis, he accepted a job offer with a firm that allowed him to take an entire year off before starting work. Out of seven job offers, one firm agreed to this stipulation (a little known fact about how we ended up moving to Salt Lake City.) During that year, we drove Betty to the southeast and spent months climbing in several states. Then we lived and climbed in Thailand for a month, followed by backpacking in Nepal for another month. After we returned, we moved to Salt Lake and bought a fixer-upper house, where we spent days of blood, sweat, and tears laying our own wood floor, tearing out wallpaper, painting, and moving furniture.

This was the sabbatical where I realized I wanted to become a doctor. It was barely on my radar before, although I had considered it during the whole transition to grad school. I knew I didn’t want to climb the corporate ladder as a chemical engineer, being dictated by the industry for where to live and making stuff instead of directly impacting lives. One freezing cold night on the Annapurna trail, I opened up my journal and let loose. After seeing life in a third world country (and extremely rural parts of the southeast US) – not necessarily suffering but just living differently – I knew that I wanted to pivot and do something involving service for a wide and diverse group of people. Before, I had also been intimidated by the idea of going to medical school, but once I trekked through snow eating nothing but peanut butter, rice and beans, sleeping in the dirt without a shower for over a week, I realized I am indeed stronger than I realize. This realization, made continents away from home, has held true through medical training and cancer and infertility.

#4

Medical school for me coincided with a time of high burnout for my husband. I remember coming home from my days feeling energized and inspired, while he sulked about his current work situation, needing to constantly convince himself that this time of intense billing was truly the training he needed to fulfill his dream of starting his own firm. Eventually, the time came for him to quit, and he wanted to travel before starting up with his own clients. I was really resistant to the idea, which required me to delay my medical school graduation for a whole year, but I got up the courage to ask, and to my surprise the dean said yes. I qualified my request by breaking the time up into two six month blocks: one block that I took between the first two didactic years and the last two clinical years of school, and one block between graduation and residency. I presented it with the idea of doing some research and community work between travels, and I blamed the need to go away on my husband.

We first went drove up through Wyoming and Montana into western Canada, then we flew to Greece and Spain, climbing a for month in each country. I completed some research projects with the Department of Anesthesiology and realized my love for the field. On the second six month block, we went to southern Mexico and again tried surfing while learning medical Spanish (some of which I have sadly forgotten). These times were a boon to our relationship and helped us to find each other again during a time when we could have easily gotten lost in our busy schedules. Many couples lead parallel lives slogging through their busyness. How can we make major life decisions as part of a partnership if we don’t take some dedicated reflection time together?

#5

The sabbatical of sorts that I took during residency wasn’t quite as rosy as the others. In fact, it was actually FMLA time and was borne out of an illness that I couldn’t understand. I thought it was burnout, and there was definitely a component of such, so I poured what little energy I had into learning as much about myself as possible, my values, and the things that help me to de-stress. I learned about mindfulness. I went on a silent retreat. I spent some time with my husband climbing in rural Colorado… only I could barely make the short hikes to the crags without crashing for a nap. My fatigue foreshadowed what was to come…

This was when I got the idea of starting the blog. I wanted to share with other professionals what I had learned on my quest for a more balanced life that avoided burnout. I purchased the domain name, but it then sat unused. As the story goes, I returned to my residency duties only to be diagnosed a few months later with a brain tumor. It changed everything: my physical presence, my relationships, the way I treat patients, my career trajectory and aspirations for the future, a mourning for the child we wanted to have put on hold indefinitely. Once my health was more stable, PracticeBalance was born.

#6

After years of infertility treaments, we finally added a new member to our family. I would also consider my maternity leave a sort of sabbatical. It definitely involved lots of work – kind of like a really bad call night that never ends day in and day out. But the joy I experienced, the gratitude, the intense love made everything feel like a vacation of sorts. I also spent some time working on me again, mentally and physically. I slowly regained my strength and body shape after a hard pregnancy by going on lots of long walks and doing (appropriately scaled) strength training, and I learned (boot-camp style) about preparation and efficiency when it comes to having a child.

* * * *

So here we are, 22 years and 6 sabbaticals later, and I’ve just gotten the go-ahead to take the next one! The time period will be September 2019 to June 2020; not sure yet exactly where we’ll be going or what we’ll be doing. We plan to take 1-2 longer trips out of the country, to places that merit staying longer than what I normally feel comfortable requesting off. Some possibilities we’re considering are southeast Asia, Australia/New Zealand, or Pacific Islands. I also plan to either do some medical mission or fill-in anesthesia work; this is not a stipulation of my agreement for the sabbatical but is rather something I’d like to do, since I’ve worked at the same hospital for so many years and feel that an experience practicing out of my comfort zone would be good for me.

Common Threads

The one thing common across all of these sabbaticals? My fear in putting the plans in motion. Sometimes I’m directly scared to ask for the approval, and sometimes I’ve just worried about at how it will appear to others. Even now, as a financially independent person who chooses to work at my job as opposed to needing to work, I still have these feelings. I still care a lot about what other people think of me. I have a serious case of what I’ve heard termed “the disease to please”, stemming from my days as a straight-A, gold star seeker to my training as a physician, which ingrained the virtue of putting your patients before yourself. I still get sad when I’m not invited to a coworker’s party. I still have stomach pangs about the good friend who ghosted me last year. I get a flush over my cheeks when I encounter a look of disapproval from another shopper as my toddler has a tantrum in the grocery store. I’m even worried that, in recounting these experiences and revealing this pattern, some of you will think I’m a hack.

Some might call what I’ve done irresponsible or selfish. I’d call it imperative for preventing burnout. If we all had more dedicated time off for self-reflection, even asked for a mini sabbatical or at least took our allotted vacation each year, maybe we’d be happier and less stressed.

“It never ceases to amaze me: we all love ourselves more than other people, but care more about their opinions than our own.” – Marcus Aurelius

Have you ever gone on a sabbatical? What was it like and what did you learn about yourself or your life?

Decidedly Non-Minimalist But Purposeful Packing

Decidedly Non-Minimalist But Purposeful Packing

Thank you for writing this! It has helped me to rethink what I’ll do after leaving my job at the end of December. Thank you for being as purposeful about your sabbaticals as you are about your career-Want to push myself to do the same in order to truly practice balance! 🙂

Thanks for your comment! I like the concept of a series of sabbaticals or mini-retirements more than just flat out “retiring”. It seems that medicine, we’re never really finished learning or helping patients. I hope even non-medical people can feel that way. Good luck!

I think it sounds wonderful! I wish I had the courage and the financial planning to take sabbaticals. Life would be a lot more interesting.

Thanks! There are always challenges in the way of making big changes like this. Courage is definitely a road block for me. I hope you can find a way to do something similar if you desire!